Indian Army welcomes the Yatris

I first tried to visit Amarnath in 2010 but could not, as the police stopped us from entering the Kashmir Valley, saying the weather was bad and driving in the high mountains was impossible. Later, we learned the real problem was locals from Anantnag and the Kashmir Valley attacking pilgrims. We were shocked and saddened to hear that we were not allowed to travel freely in our own country and that people from our own land hated us. After that incident, I promised myself not to go to Kashmir until the India-Pakistan and Kashmir issue were resolved. But the very next year, I took a road trip to Leh via the Kashmir Valley, talked with people, and learned a lot.

Viccky, Chintu, Driver and I (Left to right)

That experience changed my view and motivated me to plan another trip to better understand the people living there, their issues, and problems. My friends were planning a trip to Amarnath this June, and I immediately joined with excitement and hope to learn and experience more of Kashmir. The Supreme Court of India was very strict about the number of visitors and their health conditions. It mandated health checkups and proper registration for every pilgrim, because more than 250 people had died during the Yatra in 2012. Due to ecological concerns about the Amarnath glacier, the court also limited daily visitors to 7,500.

Baltal Basecamp

We registered and underwent health checkups in Varanasi. The process was maddening, filled with bureaucracy and typical government officer behavior. The health check included three tests: a general blood test, an orthopedic test, and a rather mysterious naked body examination. I call it mysterious because the doctor never explained why he needed to see me naked. Anyway, the blood test was fine, but the orthopedic doctor was so busy on his phone that he just stamped the certificate without a proper checkup.

Rates for tents

The naked body test was quite funny. People of all ages came out of the doctor’s room laughing or frustrated. My experience was similar. The doctor asked me to stand ten meters away, take off my pants, and cough. When I asked what it was for, he angrily told me to do it without explanation. I guess it was to check for hernia. After getting the health certificate, we went to the Punjab National Bank, authorized by the Amarnath Shrine Board, to complete the registration by paying Rs. 30. We wanted to start the Yatra from Pahalgam checkpoint but it was already full for several days, so we got permission from Baltal, the alternative. Most people prefer Pahalgam because the route to Amarnath cave from Baltal is very steep. We started our journey from Varanasi by train to Jammu and stayed overnight to rest after the 28-hour trip. We planned to reach Baltal base camp the next day.

Beautiful nature

There was heavy presence of police and army throughout Jammu and Kashmir—quite normal there. We were stopped multiple times on the way to Baltal, had to show our registration certificates and bags checked. Nearing the base camp, our vehicle was stopped at an Army camp along with around 200 others. Nobody knew why we were delayed. Finally, a polite Army man explained that locals from Anantnag were attacking pilgrims’ vehicles, so additional security was needed. After two hours, the fleet was allowed to continue, guarded by the Indian Army until we passed the sensitive area.

Pilgrims on the way to the Holy cave

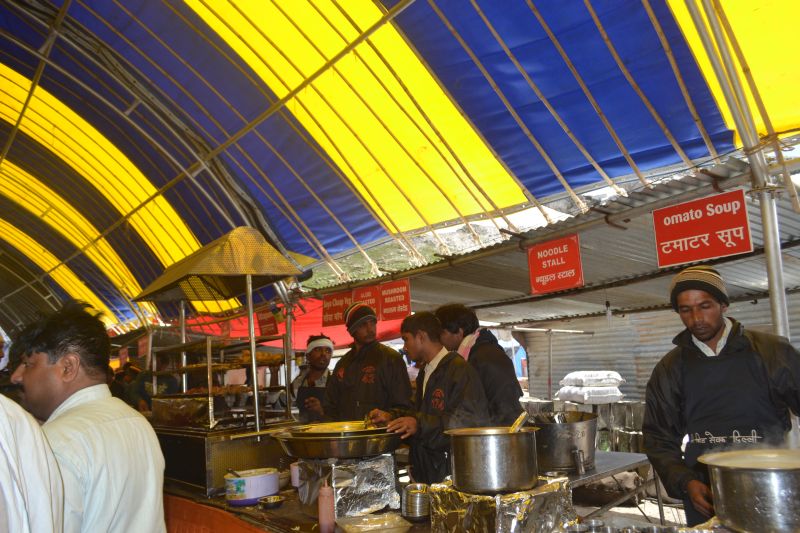

We were stopped again about 70 km from base camp and spent the night at another Army camp, where a huge langar was set up by someone from Lucknow. They provided free food, hot water, blankets, and other services for pilgrims. I was impressed by the kindness even though I didn’t eat because the line was long. We rented a small tent for Rs. 700 and spent the night, wary of the 4–5 restrooms for some 5,000 people. We left early the next morning.

I near to the Holy cave

We arrived at Baltal around 8 AM intending to start trekking immediately, but our registration was valid only from July 3rd, and we arrived on the 1st. Though others said the date didn’t matter as long as you had a registration certificate, all court orders were strict and rules followed strictly this year. Our attempts to get permission to start early failed, so we looked for langar accommodation nearby, luckily finding one run by someone from Varanasi. The langar offered us free sleeping arrangements, hot food, hot water, and clean private washrooms—a great relief. We spent the day exploring langars, meeting people, and tasting various foods.

Super crowded near the cave

The next morning, two of our heavier friends had difficulties walking in the high altitude. They opted for helicopter services to reduce the journey by 6 km, which I had never tried before and decided to join. At 7 AM, we arrived at the helicopter station, but the ticketing process was chaotic and took 7 hours since the staff used registers and no computers. Finally, we boarded a short 7–8 minute helicopter ride to Panchtarni, 6 km past the cave on the other side (toward Pahalgam).

The walk to the cave was steep and the large number of ponies competing for passage was overwhelming. Many ponies caused dust and dirt, which somewhat ruined the experience, but the nature—the clean rivers, waterfalls, mountains, snow, green valleys, and lakes—was magnificent. I walked through snow in several places along the route. At the cave, the line was huge—I waited about 3 hours to get inside. People in line talked about the holy pigeons, some saying the real holy pigeon is white, others that they are always paired. I saw at least 10 pigeons.

Security everywhere

I was excited to see the Shivalingam, but initially couldn’t spot it due to the snow inside the cave. Others pointed out a 4-foot tall piece of snow as the lingam, with other pieces representing Ganesha and Parvati. I paid my respect and left the cave. During the continuous rain and without shoes or food since morning, I felt dizzy and confused with symptoms of hypothermia—something new for me.

Inside a langar

I found a langar offering hot kheer, which felt like heaven. I felt better after eating. We decided to leave the cave area and walk back as far as possible. Our plan to reach Seshnag by night failed as the Indian Army closed the Panchtarni exit by 7 PM. We rented a tent and spent the night there. The next day, we walked back and reached Seshnag by noon. Although we could have gone faster, we took our time to enjoy nature and converse with people.

Snow everywhere

Three of us stayed overnight in Seshnag while the rest proceeded to Pahalgam, arriving by evening. A family friend, Mr. Amarpal Sharma, a member of the UP State Assembly, runs a langar at Seshnag where we stayed comfortably with private tents and washrooms. I wanted to visit Seshnag Lake, but though many stop to rest, few actually go near it. When we did, we experienced hostility—the few locals there started throwing stones and hurling abuses, some even exposing themselves to provoke us. These were mostly pony owners who make their living by renting out ponies to pilgrims. Similar or worse behavior was noticed elsewhere in the valley.

A dead pony in the lake

The environment suffers badly due to a lack of regulations. Snow turned black along the entire route from pollution, and camps discharged sewage and waste directly into rivers and ponds. Sheshnag had 100–200 camps with an estimated 4,000–5,000 people daily, all contributing to pollution. Locals said that 10–15 years ago, when pilgrimage numbers were lower, they used lake water for drinking but now avoid it due to contamination. This dire lack of waste management is seen across all pilgrims’ camps, a sad sign for such a sacred place.

It only looks clean, it has sewage in it

The camp owners share our concern and have sought government help, but none has come. Without action, the glaciers may not survive long—and without them, Amarnath itself cannot exist, as the lingam is made of snow.

Indian Army temple

For me, the greatest human feeling is harmony with those around us, and the worst is disharmony or hatred. Despite multiple visits to Kashmir, this was my first to Amarnath. I have realized the people of Kashmir generally dislike outsiders. Various groups have different demands—some want to join Pakistan, some seek independence, others dislike non-Muslim pilgrims, and some aim to convert others to Islam.

Water everywhere

This movement is so strong there’s little space for outsiders; they hate visitors. I could not enjoy because locals avoided interaction unless to sell or beg for cigarettes or candy. Poverty in Kashmir is severe; groups beg for chewing gum if you chew it, or ask for food from pilgrim camps. Otherwise, they have no interest in outsiders. If social harmony could be established, the valley’s fortunes might change in just one tourist season.

A waterfall

Kashmir is a paradise for Indians, but my experience makes not many recommend or return. Tourism could bring huge income, solving many problems, but bad perceptions spread by militants and locals hinder respect for tourists. This is unfortunate, and Kashmir must overcome it or remain poor, violent, illiterate, and unstable for many years. The great poet Amir Khusro described Kashmir’s beauty thus:

“Agar firdaus bar ru-ye zamin ast, Hamin ast o hamin ast o hamin ast.”

(“If there is a paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this.”). Despite all, nature was beautiful, and the experience was once in a lifetime. I hope someday there will be peace and prosperity in Kashmir, and people will be proud of their Indian identity, like citizens everywhere.

Bharat Mata ki Jai, भारत माता की जय